And all these together explain

why the PLAGF’s helicopters routinely violate Indian airspace in Uttarkhanmd

and Himachal Pradesh (to monitor IA deployment patterns there along the LAC); and

why China, with Nepal’s assistance, is anxious to deny India the road transportation

route via the Lipulekh Pass towards the Kailash/Mansarovar area in TAR.

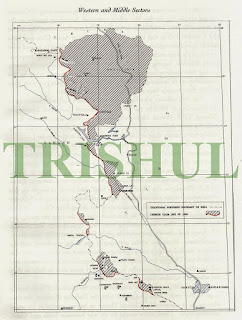

Creeping Land Encroachments Since 1956

In Ladakh, India has since

mid-1999 witnessed persistent PLA transgressions-in-strength at the Depsang

Bulge, Trig Heights, Spanggur Gap and Chip Chap Valley in

northeastern Ladakh. During wartime, the PLA’s most probable intention would be

to enter from the south of the Karakoram Range and cross the Shyok River from

the east. The PLAGF has also moved motorised forces into Charding Nalla since 2009

and these could eventually threaten the Manali-Leh route. China thus is

estimated to want to push Indian control to the left of Shyok River in the

north and left of the Indus River in the east, possibly to establish both

rivers as natural boundaries. In Chushul, the aim is to reach Luking to take

control of the entire Panggong Tso Lake. This three-pronged strategy would make

India defenceless both in the Indus Valley and the Nubra Valley.

Since 1986,

China has taken land in the Skakjung area in the Demchok-Kuyul sector in

eastern Ladakh. By 2011, it had moved to the Chip Chap area in northeastern

Ladakh. Unlike the lowlands in eastern Ladakh, the Chip Chap Valley is

extremely cold and inhospitable. Until end-March, it remains inaccessible, and

after mid-May, water-streams impede vehicles moving across the Shyok River.

This leaves only 45 days for effective patrolling by the IA and Indo-Tibetan

Border Police (ITBP). For China, accessibility to Chip Chap is easier. No human

beings inhabit the area. No one else except the Indian Army and ITBP have a

presence there. China’s probable intention would be to enter from the south of

the Karakoram Range and cross the Shyok River from the east. That would be

disastrous for Indian defence, leaving the strategic Nubra Valley vulnerable,

possibly impacting supply-lines and even India’s hold over the Siachen Glacier.

It is quite possible that China is eyeing the waters of the Shyok and Chang

Chenmo rivers, to divert them to the arid Aksai Chin soda-plains and its Ali

region. The only provocation from the Indian side has so far been the opening

of advanced landing grounds (ALG) at Daulat Beg Oldie, Fukche and Nyoma. In

eastern Ladakh, the 45km-long Skakjung area is the only winter pasture land for

the nomads of Chushul, Tsaga, Nidar, Nyoma, Mud, Dungti, Kuyul and Loma

villages. This area sustains 80,000 sheep/goats and 4,000 yak/ ponies during

winter. They consume over 75,000 quintals of tama or dry forage, worth Rs.10

crore annually. China’s advance there intensified after 1986, causing huge

scarcity of surface grass, even starvation for Indian livestock. Since 1993,

the modus operandi of China’s military incursions has been to scare Indian

herdsmen into abandoning grazing land and then to construct permanent

structures. Until the mid-1980s, the boundary lay at Kegu Naro—a day-long march

from Dumchele, where India had maintained a forward post till 1962. In the

absence of Indian activities, Chinese traders arrived in Dumchele in the early

1980s and China gradually constructed permanent roads, buildings and military

posts there. The prominent grazing spots lost to China include Nagtsang (1984),

Nakung (1991) and Lungma-Serding (1992). The last bit of Skakjung was taken in

December 2008.

China’s

assertion in Ladakh grew after it built infrastructure in its Ngari

prefecture to develop Kailash-Manasarovar into a tourist complex to attract

affluent local and international tourists. Ngari’s rapid development was a

precursor of things to come. China has thus been applying the Sino-India

Guiding Principle of 2005 to consolidate its position, for it knows that only

0.6% of the Ladakh region is inhabited. The PLA has always used nomadism as an

instrument for incursion. The migration of Changpa nomads on specific routes

has been a key component of China’s national security, something India never

understood till 2010. The imposition of multiple restrictions by Indian civil

administration authorities in Ladakh has led to a massive shrinking of

pastureland and the de-nomadisation of Changthang Ladakh, adversely impacting

national security. China wants to push Indian control to the left of Shyok

River in the north and left of the Indus River in the east, possibly to establish

both rivers as natural boundaries. In Chushul, the aim is to reach Luking to

take control of the entire Panggong Tso Lake. The three-pronged strategy would

make India defenceless both in the Indus Valley and the Nubra Valley. As of

today, the issue is not reclaiming 38,000 sq km of Aksai Chin lost to China in

1962, but retaining the territory lying inside the Indian portion of the LAC.

PLA

reconnaissance incursions into India-administered territory—by land, sea and

air—increased after 2005, with as many as 233 violations in 2008 and more than

500 transgressions from 2010 to 2012. The incursions increased after a series

of exercises were carried out in 2004 and 2005 by the PLA’s then Lanzhou

Military Region (now absorbed into the WTC), in which the PLA had theorised

that India was capable of launching a limited attack on the western portion of

Aksai Chin from Sub Sector North (SSN). In August 2009 alone there were 26

incursions in Ladakh, when the first noise was made about PLA troops painting

rocks red in the Chumur region. Chumur, near Thankung post, where the maximum

number of airspace violations by the PLA Army Aviation helicopters have taken

place, is 70km from the LAC near Panggong-Tso Lake. A PLA patrol painted China

on the rocks near Charding-Nilung Nala in Demchok in Ladakh on July 8, 2012.

Such events continued with further intrusions by China in the Trig Heights and

Panggong-Tso Lake. In April 2013, the Depsang incident took place which, by the

PLA’s own admission, was in retaliation of the Indian Army’s construction of a

single watchtower along the LAC in Chumur, a remote village on the

Ladakh-Himachal Pradesh border, which is claimed by China as its own territory

and which has been frequented by PLA helicopter incursions almost every year.

Chumur represents a deep vulnerability for the PLA as it is the only area

across the LAC to which the PLA does not have direct access. On July 16, 2013,

50 PLA soldiers riding on horses and ponies crossed over into Chumur and staked

claims to the territory and only went back after a banner drill with the ITBP

troops. This had been preceded by two PLA helicopters violating Indian airspace

over Chumur on July 11.

How IA’s Mechanised Forces Got Inducted Into Ladakh

This saga was already detailed before by Ret’d Lt Gen H S Panag here:

https://www.newslaundry.com/2017/02/10/the-road-to-ladakh

https://www.newslaundry.com/2017/02/17/the-trials-in-ladakh

It was in the last quarter of 1986 that the Indian Army, under OP KARTOOS, temporarily had six T-72M1s airlifted to Leh along with a Regiment of BMP-2 ICVs for deployment in Chushul, Finger Area and Spanggur Gap. Since the conduct of OP KARTOOS, the IA’s Karu-based 3 ‘Trishul’ Division had until 2012 just one mechanised infantry regiment—1 Guards—with 52 BMP-2 ICVs. This Regiment used to carry out regular manoeuvre warfare exercises in the Wari La region in Pangong, which is located at an altitude of 16,600 feet ASL. The IAF too had built a makeshift airstrip in Mud Village near Panggong Tso.

The then Indian Army Chief of the Army Staff’s (COAS Gen Krishnaswamy Sundarji) words—“Go to Ladakh and make history!”—were ringing in Col H S Panag’s ears as he left the conference. The burden of expectations had been placed on his shoulders and on his unit, 1 Mechanised Infantry Regiment (1 Madras Battalion). The Battalion already had an illustrious history of 212 years, but tradition and history are a continuum. It had participated in every war fought before and after Independence, it was the first to be mechanised and it was to be the first to be inducted into the High Altitude Area (HAA) of Ladakh. With these thoughts, Col Panag got down to the task of planning the induction. 1 MECH INF was to take over the 20 BMP-2s of the ad hoc mechanised force already in Ladakh. The Regiment had to induct 32 BMP-2s and three armoured recovery vehicles (ARV). The two Armoured Squadrons had to induct 14 T-72M1s and one ARV each. It required 49 sorties of IL-76MD transport aircraft (one sortie could carry two BMP-2s or one T-72M1/ARV). While the IAF had practiced carriage of medium battle tanks in plains, but landing at Leh Airport—located at 10,300 feet and surrounded by high hills—presented technical difficulties. The IAF rose to the occasion and the entire equipment was safely landed at Leh by the end of Jun 1988. Col Panag went to Ambala to oversee the airlift and also flew to Leh a number of times. He took over the Regiment in the first week of July and the Regiment was to induct by road from Jammu in the end of July 1988. This was a formidable challenge as the Regiment’s drivers had never driven in the mountains. The Regiment had a 120-vehicle convoy and on the first day, the inexperienced drivers created chaos on Highway NH-1A. The problem was solved by slowing down the speed to 30kph and Col Panag himself drove at the head of the convoy. The 800km journey to Ladakh is notorious for accidents. All units inducting into Ladakh generally meet with one or two unfortunate mishaps. However, precautions ensured that the Regiment arrived in Leh after five days’ journey, without any mishap. The Regiment less one Company temporarily settled down at Karu, 40km from Leh. One Company was to be located 120km to the East at Tangtse for deployment in Chushul Sector, which was another 100km to the East. The move of this Company by road over the 17,500 feet Chang La Pass was a great confidence builder. The BMP-2 is a unique ICV and could maintain the same average speed as heavy wheeled vehicles. Within a week, the Regiment selected the new administrative base for mechanised forces at Stakna, close to Karu. Within two months, the accommodation for the troops and sheds for the equipment were constructed: 50 troops barracks and 15 sheds for T-72M1s and BMP-2s, along with offices and messes were built in record time (two months). Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw was on a visit to Ladakh at the time and on Col Panag’s request, he inaugurated the Officers Mess and had lunch with the Regiment. As preparation, the Regiment went over all terrain and operational reports from the last 40 years, since 1947 and also studied the history of the region. Col Panag paid special attention to the campaigns of the great General Zorawar Singh, from 1834 till 1841, when he had captured a vast tract of Tibet, right up to Mansarovar Lake. In fact, he was cremated at Taklakot, near the lake in 1841. The War of 1962 was also analysed in detail, particularly the employment of the six AMX-13 light tanks that had been flown into Chushul in November 1962. The Regiment also had the benefit of the experience of the ad hoc mechanised force, which was in Ladakh since the end of 1986. The following challenges were before:

• Physical fitness and well-being of troops in HAA

• Reconnaissance of the operational area

• Evolving the offensive and defensive operational role

• Technical maintenance of the equipment in the extreme climate

• Validating the performance of the T-72M1s and BMP-2s

• Validating the operational role in field exercises

• Test exercise of the Combat Group by higher HQ.

There is a popular Army saying in Ladakh that goes like this: “In the land of the Lama, do not be a Gama (a famous wrestler).” It implies one should not compromise with the laid-down norms of survival in HAA. But soldiers must also be extremely fit to fight in this terrain. Without proper acclimatisation, there is the risk of High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema, which can be fatal. It is one of the many reasons for non-battle casualties that take place in Ladakh every year. During the Regiment’s two-year stay in Ladakh, it did not suffer any climate, fire or vehicle accident casualty during its tenure. This was because of education, adherence to norms, strict supervision and personal example. Just this achievement alone made the Regiment famous in Northern Command. The terrain of Eastern Ladakh is unique and there is no other place like this in the world. Up to Leh and 150km beyond, the terrain is extremely rugged with narrow valleys and surrounding hill ranges varying from 15,000 feet to 23,000 feet. Beyond this the valleys become broader, the base height rises to 15,000 feet and the surrounding hills and ranges become more gradual and only 3,000 feet higher than the valleys. After reconnaissance, the hill features can be negotiated by wheeled vehicles and for tracked vehicles it is a cake-walk. In fact, Major Shaitan Singh, PVC, had constructed a jeep-able track from his base at Tara Post (named after his wife) at 15,000 feet to Rechin La (at 17,000 feet), which is about 1km from Rezang La. During his reconnaissance, Col Panag drove up this road. His was the first vehicle to do so since 1962! For the Army, terrain is the most important factor in battle. For the mechanised forces, this is even more true as they must negotiate the same with 41-tonne T-72M1s and 15-tonne BMP-2s. In Eastern Ladakh, the Regiment had to not only know the valleys, but also the surrounding mountain ranges to assist the infantry units during operations. The terrain is so vast that on a full reconnaissance trip, the vehicles logged 800km. All surrounding hill-features were climbed on foot. The Regiment also climbed all infantry posts and visited all relevant LAC areas. Helicopter reconnaissance was also undertaken. In three months, the Regiment was the master of the terrain.

The Ladakh Range is extremely rugged. One had only three roads across it via Khardung La, Chang La and along the Indus River at Loma. The mountain ranges (including the Ladakh Range) are aligned in the north-west to south-east direction and the rivers run from south-east to north-west between them. This gives a peculiar configuration to the valleys and the LAC. Thus, if the Ladakh Range is crossed from Demchok and Koyul area to enter the Hanle Valley, the entire Indus Valley east of Loma is bypassed. Consequently, a road was planned from Hanle to Koyul-Demchok via the Photi La, and it was very difficult to construct. During reconnaissance and from past data, it was discovered that 10km south-east of Photi La was another pass called Bozardin La, which was relatively gradual. Riding on a hunch, Col Panag explored this virgin area and took numerous ‘S’ loops to take his Nissan Jonga to the top of the pass. There was no other vehicle with him. Taking a risk of being stranded, he gradually lowered his Jonga towards Koyul Valley. After a four-hour struggle, he reached Koyul and was on the Indus Valley. No one—including the BRO and the Col’s superiors–believed this. He proved the point after a week by taking heavier vehicles over it. Eventually, the BRO took 10 years to construct the Photi La road, but cutting a road via Bozardin La took only one year. This, of course, happened years later, but in 1988, 1 MECH INF was the first to take vehicles from Hanle over the Ladakh Range into the Indus Valley—another first! The main defences were based on the Ladakh Range and its offshoots, and the Panggong Range, west of Panggong Tso Lake. This left nearly 100km of valleys and plateaus up to the LAC unmanned. These were selectively held to delay the enemy. The Chushul Sector was more compact and there, the main defences were between 5km to 8km from the LAC. The LAC ran along the Kailash Range, which is not held either by the Indian Army or the PLA. Both sides had plans to pre-empt the other to occupy the Kailash Range in the event of war. Any reader would logically question as to why the Indian Army was not manning the LAC right up to the front, like the LoC against Pakistan. Firstly, the LAC is not active. No shot has been fired in anger since 1967. Leaving aside approximately 10 areas of differing perceptions, there is no contest from China. The LAC is selectively manned by ITBP and at places, by regular troops. Secondly, the terrain configuration offers no defensible features in the valleys. Thirdly, if the entire area was to be manned like the LoC, the Indian Army would require four additional Mountain Divisions, which is not cost-effective. Fourthly, if the enemy occupies the valleys, he would be ‘shelled out’ by field/rocket artillery and the IAF. Lastly, the mechanised forces with their mobility are tailor-made for the role of dominating valleys. In 1988, the PLA did not have the strategic airlift to land medium battle tanks or ICVs in the vicinity of the LAC. The PLA formations were located in Central Tibet, 1,000km away. Depending upon the Indian Army’s strategy, this gave 1 MECH INF a window of opportunity to pre-emptively secure the areas on or across the LAC or conduct deeper offensive operations. Mechanised forces were tailor-made for this role. Ladakh thus remains India’s best bet for offensive operations as it is an extension of the Tibetan Plateau. The role of mechanised forces in offensive operations was, as part of overall offensive plans, to pre-emptively capture the tactical features/passes on or across the LAC. Also, as per the strategic situation in conjunction with special operations forces/ air-mobile Forces, the aim was to capture areas dominating the strategic Xinjiang-Tibet Road (NH-219), which runs parallel to the LAC, 100km to the East. This was based on the strategic situation as prevailing in 1988, which remains viable till today. More so, when the Indian Army has a Mountain Strike Corps and a much larger mechanised forces of up to a Combat Command (grouping based on an Armoured Brigade with one/two Armoured Regiments and one/two Mechanised Infantry Battalions). In addition, India has much higher capability for heliborne/airborne operations. The role in defensive operations was to dominate the valleys ahead of and around the main defences, denying the PLA any freedom of action to deploy his field artillery assets and for logistics build-up. As a result, the PLA would be forced to the higher ridges on either side of the valleys. This is a classic covering-force action. Since the distances are vast, it is a prerequisite for the enemy to seize tactical control of the valleys. Securing the tactical feature on and across the LAC is part of this role. Even the PLA’s mechanised forces spearheading his offensive are at a disadvantage as the valley funnel makes him a sitting duck for India’s mechanised forces and the IAF.

The offensive and defensive roles were validated in a series of war games. T-72M1s and BMP-2s were moved to the various areas to validate their performance. The BMP-2s also crossed the Panggong Tso Lake to validate the amphibious capability. Terrain similar to the operational area in the rear areas was utilised to conduct the field exercises. I MECH INF also took part in the exercises of the infantry formations. Standard operating procedures (SOP) for technical maintenance and preservation of the equipment in extreme cold temperatures were evolved. The Russia-origin T-72M1s and BMP-2s were tailor-made for cold temperatures as long as the correct procedures were followed. At extreme cold temperatures, special oils and lubricants have to be used. The equipment must be stored in sheds during peacetime. Before starting the T-72M1s and BMP-2s, pre-heaters were used to raise the oil-pressure. If this was not done, the diesel engines would wear out (particularly accessories like the air-compressor). The ad hoc mechanised force was following the practice normal for wheeled vehicles of starting the engines every night for 1.5 hours to 2 hours, to prevent the oil and lubes and the coolant from congealing/freezing and keeping the batteries charged. While even in wheeled vehicles this is a wrong practice—tailor-made oils/coolants and batteries for sub-zero temperatures are available and pre-heaters thin the congealed oil—but for T-72M1s and BMP-2s, it was a disaster as engine life is measured in hours and not kilometres. Engine life of the 20 BMP-2s of the ad hoc force had been considerably reduced and a large number of compressors had packed up. Col Panag refused to accept the logic advanced and did a detailed study. He found that pre-heaters were not being used. In fact, drivers were not aware that they existed. Thus, the oil-pressure never reached the requisite levels and was not adequately thinned to pass through narrow tubes leading to the various components. Also, the basic starting method in T-72M1s and BMP-2s is the ‘air start’ or ‘air-cum-battery start’—the air stored in a cylinder fires the engine and in the latter case, there is also an electric spark. In emergencies, when the air-cylinder is empty, a battery start with fully charged batteries is undertaken. It was found that the air-bottles were leaking due to worn-out stoppers. The batteries at minus 20 degrees Celsius are reduced to 20% capability. Air-bottles are filled by the compressors when the engines are running. Hence, with empty air-bottles and weak batteries, the T-72M1s and BMP-2s would not start. Thus the night static-running was being undertaken to charge the batteries and fill up the air-bottles! In a nutshell, for the want of air-cylinder stoppers and charged batteries, the engines and other parts costing lakhs of Rupees were being run down. The issue was eventually resolved by simply repairing/replacing the air-cylinder stoppers to keep the air-bottle full and removing the batteries, which were kept in heated rooms on trickle charge, using generators. Also, the use of pre-heaters for 2 hours before a attempting a start was enforced. One faced no problem thereafter. All the equipment remained battleworthy. So strict Col Panag was on this issue that in winters, before a start was attempted, the driver had to personally confirm to him that the SOP had been followed! In end-1988, 1 MECH INF conducted its first field-firing and the performance of the T-72M1s and BMP-2s was validated with live fire and manoeuvre exercises on the ranges. All guns and machine guns were re-calibrated/zeroed for HAA area as they tend to fire higher. The first-generation Malyutka ATGMs of the BMP-1 ICVs posed a peculiar problem due to the altitude. Since it is manually guided, it tended to take off high into the sky. A drill was evolved to take a ‘down’ correction with the joystick to correct the same. Second-generation Konkurs ATGMs of the BMP-2, which have automatic guidance, posed no problem. The passive night-vision devices, which work on the principle of enhancing the ambient light, gave the Regiment double the distance due to higher ambient light in HAA even on moonless nights. This was a force-multiplier. The awesome firepower of the Combat Group—which consisted of 28 125mm 2A46 tank cannons, 42 73mm cannons of BMP-1s, 10 30mm cannons of BMP-2s, 104 12.7mm machine guns of the tanks and BMPs and 52 ATGM launchers apart from the infantry weapons of the Mechanised Battalion—was demonstrated to the Division. The firepower of the Combat Group was more than the combined firepower of the entire Division in terms of direct-firing weapons. This was done to inspire confidence in all troops. The crowning achievement was the test exercise attended by the GOC-in-C Northern Command, GOC XV Corps and GOC 3 Infantry Division, who was testing 1 MECH INF. The Regiment came out of the test exercise with flying colours. GOC-in-C Northern Command said: “The Combat Group has made history. The foundation for the employment of larger mechanised formations, which will give us the desired offensive capability, has been laid!” The Indian Army had to wait for another 28 years before the induction of Combat Command in 2016 to get the enhanced capability. Though the ideal eventual requirement is of two Combat Commands and two Motorised Infantry Divisions! Such a force would give India the “retributive capability” a major power should have.

Captain B H Liddell Hart, the famous military historia, had once said: “The only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind is to get the old one out.” Having stopped the static-run of medium battle tanks and ICVs in 1988, Col Panag next wrote a detailed SOP for maintenance and preservation of tanks and BMPs in HAA and sent it to all concerned, including a copy to all Mechanised Infantry Battalions and Armoured Regiments. In January 2000, Brig Panag was Brigade Commander in Batalik and came to know that the old practices had restarted. He spoke to the XV Corps Commander—who dug out his SOP—to stop it. In 2005, as Corps Commander, Lt Gen Panag visited Ladakh and found that the old practices had commenced again. Once again, he got it stopped. In 2007, when he became GOC-in-C Northern Command, to Lt Gen Panag’s horror he found that it had recommenced due to change of units and the SOP being buried under files. Once again, he got fresh SOPs written to enforce the same. In 2016, a Combat Command was inducted into Ladakh. During his visit to XIV Corps, a now retired Lt Gen Panag briefed the staff in detail.

Though the Indian Army had deployed 30 T-72Ms in the Daulat Beg Oldie sector in eastern Ladakh, bordering China. The field commanders thought such MBTs were of no use in the mountains as the PLA was then not even patrolling the disputed LAC. The MBTs were dismantled and moved to Leh, and flown to the mainland in IL-76MD ‘Gajraj’ transport aircraft. In mid-2009 a decision was taken to introduce six T-72CIA A-equipped Regiments (58 tanks per regiment, including reserves), equipped with 348 tanks. In addition, three new Mechanised Infantry Battalions with 180 BMP-2s were to be raised. Thus, the Ladakh-based XIV Corps was to be allocated an Armoured Brigade to cover the flat approaches from Tibet towards India’s crucial defences at Chushul. In addition, one Regiment was to be located on the flat, 17,000-feet-high Kerang Plateau in northern Sikkim. In 2014, HQ Northern Command started the hunt for a Brigade (army formation with close to 4,000 troops) which could be deployed at altitudes higher than 15,000 feet. It soon realised that the 81 Brigade, aka the Bakarwal Brigade, could be sent to the Daulat Beg Oldie sector with an Armoured Regiment. Combined, they could defend a possible armoured invasion by the PLA, launched through NH-218. IAF Boeing C-17A Globemaster-IIs took off with T-72CIAs from the Chandigarh air base. The C-17As, which can haul 77 tonnes each, were bound for Leh. The Hindon-based C-17As were used to send the tanks and ICVs to Leh, from where they were sent to Daulat Beg Oldie and other areas in eastern Ladakh. Around 100 T-72CIAs were sent for equipping the the 85 Armoured Regiment at Nyoma and 4 Horse at Thangtse. With these in Daulat Beg Oldie and the Depsang Plain, the Indian Army can now cross the Demchok Funnel (where the Indus River enters India from Tibet) and intercept NH-218 in case of hostilities. 81 Brigade is presently headquartered at Durbuk—14,000 feet above sea level—near Daulat Beg Oldie and en route to the disputed Panggong Tso Lake. Under 81 Brigade, three Infantry Battalions (with close to 900 troops each) have been deployed in the area. This is in addition to the 114 and 70 Brigades, which are part of the 3 Infantry Division. The Siachen Brigade was formerly under 3 Infantry Division. But, now the Division has been relieved of its responsibilities in the Siachen Glacier and has been asked to focus on the LAC with China. The Siachen Brigade is now under the Leh-based XIV Corps.